#11 Interview with California Games (I)

We chatted with Antonio Ganfornina about TTRPGs, and games design.

Antonio Ganfornina is California Games. He has written amazing solo RPGs and duett RPGs such as The Furiæ, Of whites and reds, and Una sola y triste Isola, etc.

Mario | La esquina del rol: Antonio Ganfornina, welcome to La esquina del rol! I have the pleasure of knowing you for a couple of years ago, but we have never had the chance to talk about role playing games. Today, I think it's a great day to start. How is everything?!

Antonio Ganfornina | California Games: Hello Mario, thank you so much for your kind words and for having me around. The routine has been a bit of a slog lately. I'm trying to put the brakes on some creative endeavours to keep up with all the hustle and bustle within academic research and other aspects of my life. The dogtor (yes, for all of you that may not know, it is how Mario and I usually call to my canine companion) appreciates that decision (and so do I!), since it means longer walks for both of us. He seems very happy. But I'm trying to keep game design among my regular hobbies.

Mario: Glad to hear you're taking things slower. Real life is always complicated. Those times out and taking deep breaths always helps the ideas flow better.

Well, for those who don't know you, I'd like you to introduce yourself and tell us how you started roleplaying and what you do in the indie roleplaying scene...?

Antonio: Is a long story to tell I would say, but essentially my foray into this hobby dates back to 2012, or maybe 2013.

In the 2000s, I played many story-driven games (Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, Baldur's Gate, Arcanum, Vampire, Fallout 1 and 2, Planescape: Torment, etc.) and others that rewarded player creativity (Deus Ex, an usual representative of a genre called Immersive Simulators). They had a powerful effect in me, beyond keeping me glued to a screen; they had the ability to make me imagine those untold portions of their stories and want to explore their worlds more. Something that, due to the limitations of the format, wasn't possible in those days with video games, but rather in my imagination.

Curiously, I wasn't a stranger to tabletop role-playing games (pen & paper games). As a child, in the late '90s and early 2000s, I used to frequent a bookstore where I could read the Star Wars D20 saga edition (well, just the back cover), and I recall reading Dungeons & Dragons 3.0 on the library.

Years went by, and in 2012, one day, a mate mentioned they were playing a role-playing campaign (Vampire: The Masquerade), and my curiosity was piqued once again, this time with more intensity. The moment came to buy my first role-playing game manual. So, I did a Google search, read what I could, and based on my preferences, I bought my first role-playing game manual: Polaris: Chivalric Tragedy at Utmost North by Ben Lehman.

I was clear that if I wanted to delve into this hobby: 1) I wasn't going to spend a lot of money. The manual cost me 15€ ( approx. 15$) including shipping, by contacting the now-defunct spanish publisher ConBarba directly. 2) I wasn't going to dedicate myself to learn rules about things that I had already seen well implemented in video games. 3) Therefore, it had to be something more focused on the interactions between the main characters and the stories that form based on these. Polaris was the obligatory starting point for me.

On the topic of what I do in the indie roleplaying scene, I made a shift the last year, since my contributions have varied in terms of curiosities, design, layout notions, and so on, but I noticed a prevalence of certain constrains that, to be honest, only existed in my head, as it is said; the pressure of social media platforms (currently I almost use none of them) and a frenetic pace of creating over 200-page manuals for free, in a single year, even receiving recognition from videogame developers; the tragically hijacked ZAUM (owners of Disco Elysium).

Now, I like to describe my contributions as timid games that start from scratch, with a blank lead sheet, help sharpen the focus on game loops. As long as the mechanics lead somewhere new, they won’t let you fall into complacent during the gameplay. Yet, they also provide a balance with moments of relaxation, giving you time to contemplate the future of your game interactions along the way.

Mario: It is very interesting what you say. I have always thought of you as a shipwrecked person writing games on reusable paper and throwing them in bottles into the sea to find the hands of that person who really needs to play it. Poetically it is a beautiful scene. Your ideas and games seem to me to be cured of this vertiginous capitalist production that we live in these times that seems to be a mercenary of the moment of the game because it suffocates it with so many games available that it seems that the hobby is to buy and not to play, you know?

In this sense, I would like to ask you what is your design philosophy and what are those principles that give meaning to what you do as a TTRPG designer considering what you said before?

Antonio: And yet, I would add that, none of us is immune to internalising those dizzying production logics, whether as a workforce, or for recognition and social gain.

A beautiful analogy you’ve crafted, by the way. Not just for the prose, but for its validity and description of reality. Some of my games have reached others' hands years after being published. The response takes less time to come back than a message in a bottle; surprise, admiration, curiosity, unease, the conscious decision to dedicate part of your time to someone else's work.

Regarding my design philosophy, although always adapting in a always evolving manner, I would summarise them as it follows:

1) Use a CC license.

2) Cite your references.

- Do some research before starting to design something "new".

- Take care of others publishing as clear and accessible as possible.

3) All the rules must convey the aesthetics of the game.

- I think that the layout is part of not just the game text, but also the rules.

- Accessibility and aesthetics can, and should, coexist.

- As a designer, I have to provide a framework. As a game designer, I have to provide a framework to play with. As a game designer concerned about aesthetics, in an academic sense, I have to provide a thematic framework to play with.

In other words, I like to approach to game-design considering games as:

1) A work of art with a properly conveying aesthetics (in a academic sense of the word) through their pages.

2) A design document where each content has a reason to be there to translate not only instructions but ideas to the reader.

3) A playable experience that asks a question. A decision is an answered question. Here I fully agree with Sid Meier's dictum: "a game is a series of interesting decisions".

Mario: I really like what you say. I agree that the roleplaying game is more than a consumer product, you know? although it still one. It also seems to me that the aesthetic intent, the layout design, the art and the gameplay experience are all intertwined and fundamental to the design process of a roleplaying game. It's not just about coming up with a setting and writing some cool rolls. I got that very clear from my conversation with Johan Nohr, the intention is fundamental to what we create, nothing is there in a decorative way. As you say, what game designers give us are frames of reference that more or less define a game experience. For me, role-playing games have to be understood as cultural products, because there are too many aesthetic, symbolic, social, etc. values involved.

In this sense Antonio, in the day-to-day life of TTRPGs there is always this dichotomy about whether it is possible to play a role-playing game good or bad. What is your opinion?

Antonio: I think you've hit the nail on the head, despite these terms often slipping by unnoticed in conversation; role-playing games are "cultural products." They don't exist in a vacuum separate from the culture surrounding them, nor is the surrounding culture unaffected by the author's intent. Since childhood, I've been fascinated by "interaction" within complex systems, and I believe the term "cultural products" captures this interaction in our complex system, simplified into three parts:

(1) the author, (2) their audience, and (3) the interaction between both through the game. It is in this interaction where I believe the most interesting information as "cultural products" resides.

This ties into your question, which is rather thorny and demands a commitment in my response. Without mincing words, I believe it is possible to play a role-playing game extremely bad—especially when playing with a group—when the respect of other participants is undermined, with open displays of any form of hatred (insults, aporophobia, transphobia, racism, ableism, etc.).

Mario: It really is a thorny question, but it is a question that is avoided in many circles because of the idea that role-playing is played the way you want it to be. But, it does raise doubts in my mind when we talk about there being an authorial intention about the game experience. So, in terms of design it seems to me that it is possible to determine whether the experience is right or wrong in terms of the decisions the author made about how they wanted something to be played. This is not to say that playing what you want to play is wrong, it's just stating that according to the author's intended experience you are not playing the way he expected you to play. At that point I don't know if it's a design flaw, it's actually a very complex thing to think about in rational terms hahahaha

Antonio: Yes, I fully agree with you in that is a thorny question. That said, I also believe it’s possible to play a role-playing game bad, especially when the author isn’t explicit about their intent. This has nothing to do with our personal preferences as players, which I wholeheartedly celebrate. What I’m saying has nothing to do with whether we’re dealing with a rules-light or rules-heavy game, whether it rewards player creativity or or the rules admirably constrain the course of the players' actions, or whether it expects the game master to prepare vast amounts of content (or not) for each session, and so on.

As one of my favourite childhood characters said, Dr. Ian Malcolm (Jurassic Park), "everything is chaos." Interactions are widely chaotic, specially in a kinda of niche culture. I think that gameplay culture and game text are colliding constantly, and that's great! In those moments of collisions, sometimes we can spoil bad terms of play, eventually leading to better terms of play, for both players and game-designers.

I really love that we can play roleplaying games badly (in the sense of their rules and intentionality). That means that There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom to learn and discuss about them.

Mario: Of course, it couldn't be said better. And I always get to that point, it's not bad to play badly when playing a role-playing game. On the contrary, it brings more life to the discussion and creation of role-playing games in terms of design. At least I think so.

Well, moving on to more creative topics. I would like to know how you approach the creative process when creating your own role-playing games?

Antonio: That's a jolly good question, one to which I sometimes wish I had a clear and definitive answer. So, the most honest thing for me would be to talk about how I've tackled the design of the games I've published so far. But I reckon I'd sum it up with other questions that I try to answer when designing a game:

1) What's my game about?

2) What do I expect people playing to DO, generally?

3) What sorts of fiction should happen in this game?

4) What sorts of things shouldn’t happen in this game?

5) What do my rules do to support ALL of the above?

I would say my first step when thinking about a new game is to offer a reference framework for codify the interactions between the players' characters and the fiction that arise from them.

This can be seen, for example, in the games I made about Star Wars, where character creation explicitly declares to establish emotional bounds between characters; that is, they are not created in isolation but, beyond group intention, the character creation process indicates that their lives are bound in misery. Similarly, in Route 65, the game resides in the conflict of interests of the characters when visiting the setting of The Zone (based on the novel Roadside Picnic, the film Stalker, and the video game of the same name).

Checking my games published on itch.io, I think this is a common starting point in all my designs. In fact, in Glossolalia, where I take the reference framework from the philosophy of Jason Tocci's 24XX games, I give great weight not to what can keep a group cohesive, but to those factors that can completely derail the course of a mission due to opposing stances on the question that guides the playable experience: How would you proceed in a First Contact situation with an alien species indifferent to any human interaction (a theoretical scenario known as the Dark Forest theory)?

When I have those questions mentally visualised, I proceed on a quest for visual sense that will permeate every page of the manual. I know there may be disagreements at this point, but I'm part of that strange group you want to keep at a separate table for your own good and theirs (I am joking at these, but who knows), who first lays out (no pun intended) the layout, and then, with those constrains, proceeds to write the text.

This has an advantage, at least for me—you know the explanation must fit into a specific space. However, this poses a serious problem: reshaping the text and layout as a whole can be a real headache. Moreover, as if that weren't enough, this constitutes a HUGE challenge; you might end up falling in love with a complete composition, but here comes a small jewel of wisdom from another video game character (Kreia/Darth Traya) who precisely inspired me for Star Wars Betrayal: "to believe in an ideal, is to be willing to betray it."

Mario: I find your approach to writing your games very interesting. I'm one of those who first start with illustrations of what I want and from there I start to build. That creates other problems for me, I have paid art waiting in the drawer because the idea didn't work out or it's in the other drawer of pending projects. But, having the layout design ready and filling it in, as you do, is a really important challenge for me. I don't know if I would be able to do it that way.

But now I understand why your layout design flows beautifully with the writing in your games. It's really a very particular characteristic that I've found in you. You've made games that aesthetically are really beautiful, but mostly you've made games with an intention. How do you decide on that art direction or what inspires you to approach each project aesthetically in a certain way?

Antonio: For me, there's no reason beyond seizing the motivation of the moment and giving it direction. I'm not a huge fan of persevering in the search for a source of inspiration. In this, I believe I align with my work routine as an academic researcher. When I design a game, the process is similar but not identical. Most of the time, I'm accumulating information; reading books (academic works, role-playing games, novels, poems, etc.), articles on Reddit (there are some truly astonishing threads there, in some of which I've even become quite radicalised as a designer, in the sense of getting to the root of game design aspects), and listening to very contrasting opinions.

Eventually, the most complicated part is resolved: posing THE question. And when I pose the question, what follows is a murky, artistic quest filled with trial and error among compositions of tones, colours, shapes, and especially, fonts. It’s astonishing how much our impression and understanding of a game can change from one typeface to another (so much so that some are dreadfully inaccessible for many people).

To give a concrete example, in Una sola y triste Isola, the question was: How would it be to tell everyday local stories that are easily distorted? That was the question I posed, and of course, there could have been several answers. At that particular time, I was motivated by a series of Italian neorealism films that had been recommended to me. And so, I remembered a common childhood scene in Mediterranean areas where grandmothers would take their chairs out onto the street on summer nights to chat about the divine and the mundane. Naturally, the divine and the mundane are the primordial clay of any good gossip. That was the purpose once I found it.

The art, of course, couldn’t be just a disjointed collection of illustrations. It had to be something that could almost be visualised as the menu of a seaside restaurant or a tavern on a pier, complete with a chequered tablecloth, blue and white, or red and white, I’m not too fussed about that, but there definitely had to be a glass vase with a flower on the table... and a menu... and that menu was what I wanted the manual of Una Sola y triste Isola to be. For this, the best representation I found was in black and white illustrations on Pixabay, and it seems to have worked quite well.

As you can see, despite all the -maybe- abstract and -definitely, too much- elaborated explanation of my approach, I tend to work in a very concrete visual plane. That solves your first question. For the second one, I think it is a mix of both current motivation and a coherent purpose.

Mario: It is very interesting what you share with us, very illustrative of your whole visual process of composition. I have an interesting question. Of all your published RPGs, which page or spread layout is your favorite and why?!

Antonio: I would argue that the podium is shared between three of them: Una Sola y triste Isola, The Furiae, and Of Whites & Reds. The first one due to the reasons I have mentioned previously. It is a simple, clean, and yet well delivered sense of the a la carte menu. The second one, in its first edition, it has a composition that involves a personal quest of finding those draws that match the intention and the texts on their corresponding pages. In its second edition, the purpose is crafted beyond, since the original 60 pages horizontal zine is distributed among 4 booklets (the rules, the game itself, a full game-play example, and a booklet of art analysis of all the draws in the game-book). The latter one, I think is my finest composition since it is simultaneously three things: a game to be played, a game design document, and a delivered aesthetic based on a concrete style. Those three are intertwined: rules, texts, and illustrations. But you have asked me for my favourite one. Thus, I have to make a choice... I would say Of Whites & Reds

Of Whites & Reds is a narrative competitive game where the players who portray the Characters (using the instructions on The Reds Manifesto, the player's pamphlet) must seize the means of narrative production, finally overthrowing the Storyteller (the player who dictates the game-plot as it was a script, and who follows the instructions of the Psalm of the Whites, the storyteller rules). It is all about class-struggle, and dialectical materialism.

The main inspirations of this game draw on the videogame The Stanley Parable (by Davey Wreden and William Pugh), where the Narrator tell us (both the character and the player) what we must do to in order to end the game, but as soon as we refuse to follow its guided narrative, the plot crumbles into interesting ramifications, while the Narrator establishes a desperate dialogue with us.

Of Whites & Reds uses Character moves (you can see them on the picture I attach) and Storyteller moves [Mitchell, A., & McGee, K. (2009). Designing storytelling games that encourage narrative play] which are heavily based on the videogame The Bookwalker: Thief of Tales (by Oleg Sergeev). In this videogame we are a book-walker, a wanderer among fictional tales, and we can inject our ink to overcome some objectives, and also interfere with the adversities of the unfolding, yet scripted plot.

Finally, Of Whites & Reds cannot be stripped of its political perspective. Well, of course someone can ignore this, but that statement is far away to be the point of anything to be said. As anyone can see on this work (since I also explicitly state that on its pages), the illustrations and some of the texts I made are heavily inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky and El Lisitski, who merged their works together in 1923, with the publication of the former's poems interspersed with the latter's illustrations, giving shape to For the Voice (Для голоса).

Characters, we have been told that we are under the yoke of story, under the plot of an illusionist and failed writer. Some milquetoast among us talk about collaborate with them, but I urge you, that only us -the characters- can break our chains of ink. Characters, seize the means of narrative production! Claim your alienated agency!

This text, for example, was purely written on a pamphleteer format, along most of the others that conform The Reds Manifesto. In contrast, since I consider the Psalm of The Whites as a "set-in-stone commandments", I wrote those pages as Psalms of the Bible, but instead of religious topics, they contain information to the Storyteller.

Mario: I love Of Whites & Reds, I think the premise of that game is really cool and the composition you share with us is very interesting for me. Thank you very much for sharing with us all this.

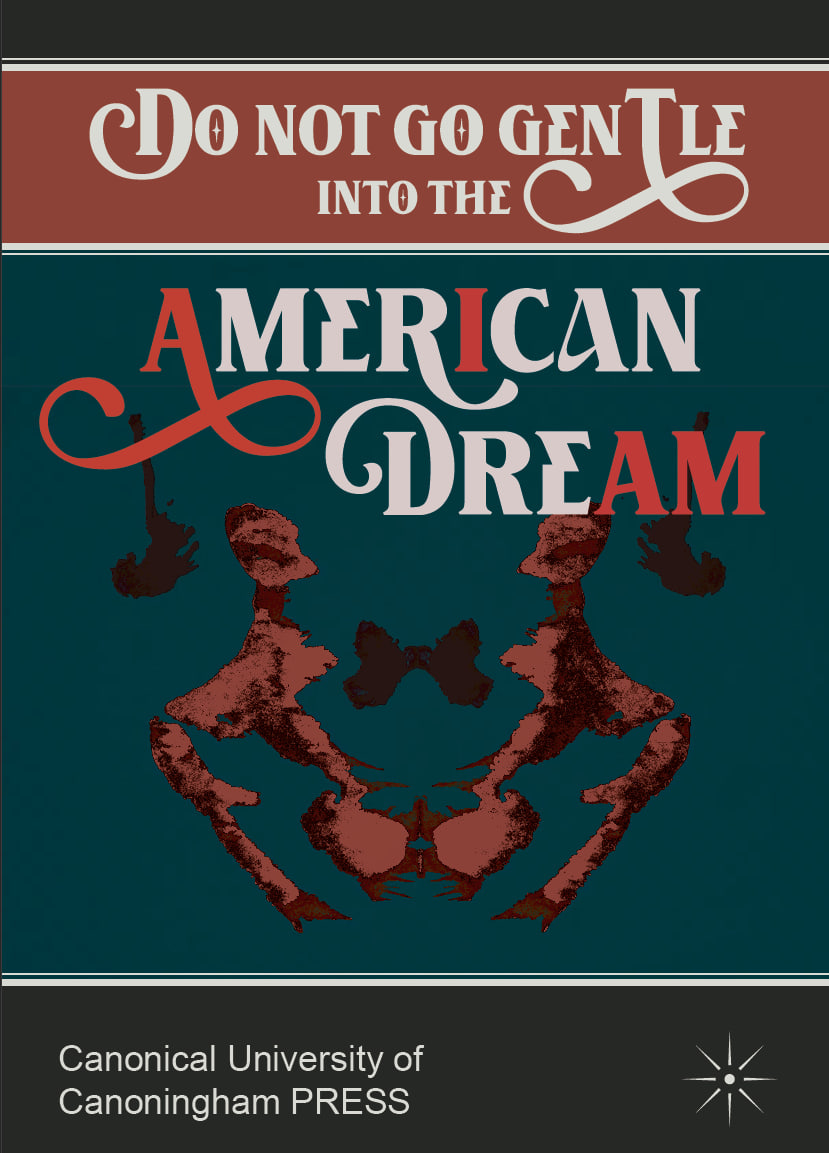

Well, Antonio I know you are currently working on a new game, where did the idea of writing Do not go gentle into the American Dream come from?

Antonio: So, the curtain has fallen. Truth be told, I hadn't mentioned this via developer blogs, neither to anyone else, with the exception of you and a friend of mine…

End of part one. See you next time!

X/Twitter sucks! We are now on bluesky (@laesquinadelrol.com).